NH Without Maple Syrup?

How Climate Change Could Make Local Sugaring a Relic of the Past

Climate change means biodiversity change. And the faster it happens, the faster local food crop species, such as Acer saccharum, the sugar maple, are losing their health and habitat.

According to the U.S.Geological Survey, temperatures in the northeastern U.S., perhaps due to our proximity to the warming Atlantic Ocean, are increasing much faster than the global average, such that the 2*Celsius (3.6* F) temperature rise expected this century will be reached 20 years earlier in New Hampshire.

These effects have already been seen in the NH sugar maple industry (ACERnet data). Our tree-tappers are already aware of increasing seasonal variability in the run of sap, with a trend towards earlier and/or shorter tapping seasons. Together with the science showing that our hotter summers means a decrease in the sugar content of sap, less sap with less sugar means less syrup per tap, and a predicted 25% drop in yield by 2050 (usgs.gov).

The quality of the syrup is also changing. Climate change is prompting a shift in the phytochemicals produced by the trees, leading to more dark grades in our NH maple syrup (ACERnet data).

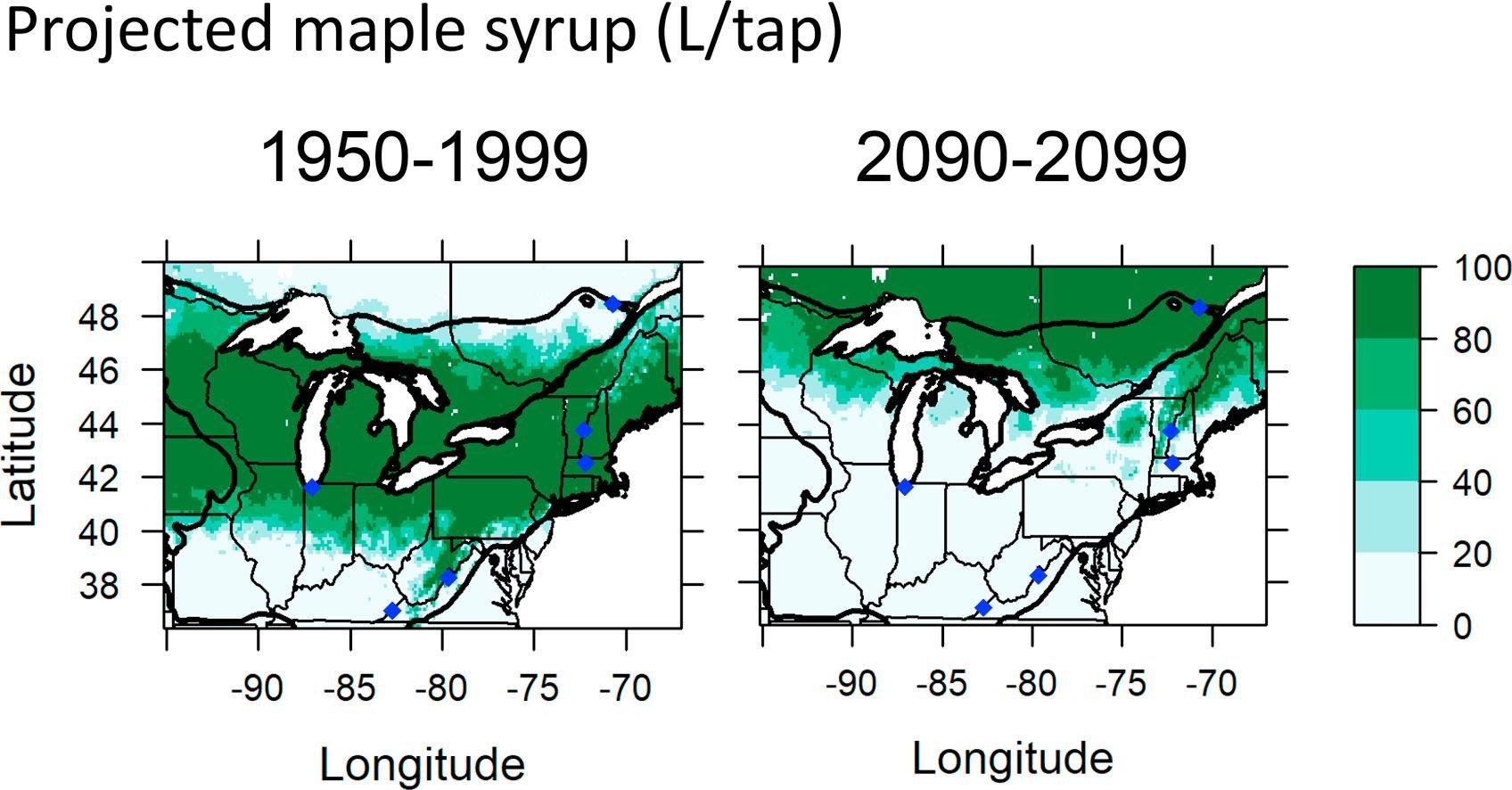

With the already established declining sugar maple habitat in New Hampshire, expert analysis has predicted that higher syrup collection per tap, previously enjoyed by New Hampshire, will shift northward into Quebec. In the past, the 43rd parallel (southern NH) has been the sweet spot. By 2100, this will have shifted north to the 48th parallel (mid-Quebec), resulting in a 50% drop in NH syrup yield (Forest Ecology and Management 448(2019) 187-197).

In sum, climate change is pointing New Hampshire towards:

Fewer trees

Reduced tree health and growth

Shorter tapping seasons

Decreased sap and syrup yields

Decreased quality of syrup, and

Further loss of market share to Quebec.

Maple syrup production is already ending in Virginia. How many more generations will see maple syrup produced in New Hampshire? And is this an example of future loss of other local food and fishery crops?

Paul Friedrichs, MD